|

INTRODUCTION TO THE

FILMS OF KIDLAT TAHIMIK:

ON THE POLITICS AND AESTHETICS OF FILIPINO CINEMATIC ART

By E. SAN JUAN, Jr. |

Pigafetta mentions the slave about five or six

times.... Possibly the first man to circumnavigate the world was a

slave...a Filipino. -- Kidlat Tahimik

Foreword

Despite having won numerous international awards, Kidlat Tahimik

(Eric de Guia) remains virtually unknown except for a few film

aficionados. Recently his name appeared in Manila newspapers when

his 4-story "Sunflower" house in Itogon, Benguet, burned down. His

sons escaped, but his precious collection of art was destroyed.

Built by his father from recycled wood in 1972, the house is

symbolic for Kidlat: "Only a charred sculpture of an Igorot man playing

the flute remains of the house. It stands by the gate. I lost all

my memories in that house" (The Manila Times, Feb. 16, 2004).

It can be said that Kidlat's films all deal with memories of

creation and destruction. They embody historical recollections of

the national past accompanied by a critical inventory of what is

important and meaningful to be saved for the future. This essay

intends to explore the method in which the colonial past of

Filipino society, its current crisis, and problematic future has

been translated into visual tropes and symbolic figures in

Kidlat's two films, Mababangong Bangungot (Perfumed Nightmare, 1977, 91

minutes, winner of the International Critics Award at the Berlin Film

Festival Award), and Turumba (1981-83, 94 minutes,

winner of the Top Cash Award, Mannheim Film Festival). My comments are

meant to provoke questions and arouse interest in the topic of what

constitutes a properly Filipino cinema.

It can be said that Kidlat's films all deal with memories of

creation and destruction. They embody historical recollections of

the national past accompanied by a critical inventory of what is

important and meaningful to be saved for the future. This essay

intends to explore the method in which the colonial past of

Filipino society, its current crisis, and problematic future has

been translated into visual tropes and symbolic figures in

Kidlat's two films, Mababangong Bangungot (Perfumed Nightmare, 1977, 91

minutes, winner of the International Critics Award at the Berlin Film

Festival Award), and Turumba (1981-83, 94 minutes,

winner of the Top Cash Award, Mannheim Film Festival). My comments are

meant to provoke questions and arouse interest in the topic of what

constitutes a properly Filipino cinema.

Since 1983, Kidlat has been experimenting with a film entitled

"Memories of Overdevelopment" about Pigafetta, the Malayan slave

who lived after Magellan's death and circumnavigated the world.

Meanwhile, he has just completed a semi-autobiographical film,

Bakit Yellow ang Gitna ng Bahaghari ( Why is the heart of

the rainbow yellow? 1980-1994, 175 minutes). Aside

from personal reminiscence, the film also tries to capture the

texture of political life in the Philippines from the dark days of the

Marcos dictatorship, the "People Power" revolution that overthrew

the brutal regime, the turbulent period of Corazon Aquino's rule

and the atrocities committed by vigilantes, up to the withdrawal

of U.S. military bases, the earthquake that devastated Baguio

City, the Mt. Pinatubo eruption, the energy crisis of the

nineties, and the revival of indigenous movements by the end of the

century. It is a panoramic photograph of a historical sequence in

the vicissitudes of a neocolonized people/nation in the process of

self-emancipation.

The Perfumed Nightmare

For those who have not seen the two earlier films which I analyze

below, allow me to describe them in broad strokes.

Perfumed Nightmare involves Kidlat's awakening from the "cocoon of

American dreams," a span of 33 typhoon seasons since his birth in

1942 during the Japanese Occupation. The "perfumed nightmare"

refers to his existence in the lotus-land of American cultural

colonialism. By using the jeepney, a recrafted vehicle left by World

War II GIs, as a symbol of the historical passage from the past to the

present, the Kidlat persona in the film crosses "the bridge of

life" into the village where normal routine is defamiliarized for

him by his listening to the Voice of America broadcasts. This

obsession becomes

catastrophic but also educational.

Fascinated by America's space program, Kidlat becomes the head of

a Werner von Braun fan club. His enthusiasm for progress leads to

his managing for an American businessman a chewing-gum ball machine

concession in Paris and Germany. After a parodic enactment of a summit

meeting in Paris, the film leads to Kidlat's disillusionment with

progress; he finally realizes that machines and efficient

technology destroy certain values necessary for human freedom and

happiness. He returns to his village, resigning from the Werner

von Braun club, and affirms that he will find his own way to liberation,

even though the idealized past of pre-colonial Philippines cannot be

restored.

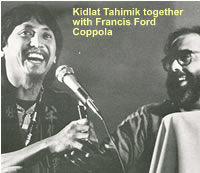

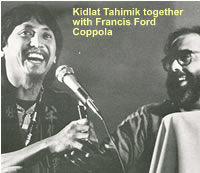

Hallucinatory, naively accomplished, humorous and surreal,

Kidlat's fable supposedly demonstrates the native's magical prowess

of producing a substantial art-work for only $10,000 (the cost of the

outdated film stock), with the help of Werner Herzog and Francis

Ford Coppola's studio Zoetrope which distributed the film.

Turumba

Turumba is actually Kidlat's first film. It focuses on one

family's traditional occupation of making papier-mâché animals for the

Turumba religious festival in a Filipino village. Everything

changes when a German agent buys all their stock and orders more

for the Oktoberfest celebration in Germany; soon the family's

seasonal occupation becomes a year-round routine of alienated

labour. Eventually the whole village is converted into a jungle assembly

line to produce papier-mâché mascots for the Munich Olympics. With

the intrusion of electric fans, TV sets, Beatle records, and the

compulsion of work schedule, the

traditional rhythm of family and village life is irretrievably broken.

Success for the family coincides with the emergence of a local

proletariat whose innocence is ironically shrouded by the

turbulent storm, emblematic of the revolt of nature, that overtakes the

whole village. Is this the judgment of a subliminal conscience, or

the ironic comment of a sagacious historian? J. Hoberman

remarks that the film is "not only amusedly Marxist but mock

German in its low-key nostalgia as the old-time völkische

gemeinschaft succumbs inexorably to the bad, new gesellschaft of

industrial civilization." Just as the first film rejects modern progress

and its dehumanizing effects, Turumba laments the passing of the

old sacramental unity of man and nature, opting for a middle way

of compromise: the bricolage of the film-maker, reusing the past

to renew the present and thus initiate a more imaginative,

organic, integral future.

Both Perfumed Nightmare and Turumba use realist scenarios to

project an allegorical rendering of the Filipino experience under

U.S. colonial domination and its disastrous neo-colonial sequel. What

engages my interest here is the vision of the future inscribed in the

films, and how their cinematic methods may hopefully allow popular

energies to intervene in blasting the burden of the nightmarish

status-quo--the legacy of colonialism and corporate globalization

-- which Kidlat addresses more directly in his more politically

astute concoction, Bakit Yellow ang Gitna ng Bahaghari (Why is the

heart of the rainbow yellow). On the latter film, we can

postpone our commentary for another occasion.

Revisiting the Primal Scene

The controversy over the bells of Balangiga in 1998, the year of

the Centenary of the First Philippine Republic, may yield more

than a journalistic and diplomatic fruit. It offers an unsolicited

pretext to explore the implication of certain appraisals of Kidlat

Tahimik's film art, in particular, The Perfumed Nightmare, and its

post-modern resonance. This somewhat gratuitous timeliness may in turn

open the closure of ludic Eurocentric postality to its victims. At

least, this will counter the post-modern amnesia regarding U.S.

imperialism.

Shortly after General Emilio Aguinaldo revolutionary forces

inaugurated the Republic in 1898, the Filipino-American War broke

out, resulting in the death of about a million Filipinos, the

destruction of the nationalist government, and the U.S. colonial

domination of the Philippines for over half a century.

One of the few incidents in which the Filipino revolutionary army

inflicted a devastating defeat on the United States expeditionary

forces was the attack at Balangiga, a town in Samar province, on

September 28, 1901. Of the 74 soldiers in the 9 Infantry Regiment of the

U.S. army stationed at the town, 45 were killed and 22

wounded--almost the entire regiment. In retaliation, Gen. Jacob

Smith who commanded the Marine battalion sent to reinforce the

U.S. occupation troops ordered a mass slaughter. The interior of

Samar must be made a howling wilderness (Vizmanos 1989: 14). This

unofficial U.S. policy of indiscriminate pacification made the War an

unpremeditated rehearsal of Vietnam and a template for the colonial and

neo-colonial subjugation of Filipinos for the next century. We have not

yet fully recovered from the effects of that howling wilderness

which becomes, in Kidlat's film, the roar of rocket ships and

destructive machines.

When the American veterans of the Indian Wars and the Philippine

pacification campaign returned, they brought with them three bells

confiscated from the Catholic Church in Balangiga two of which are

kept at Francis Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne, Wyoming. On the

occasion of the Centenary, the Philippine government requested

Washington to return one of the bells and a copy of the other; the

military has so far refused. A retired general who is civilian

adviser to the base justifies the refusal: We don't have to

rewrite history and give back the bells because, yeah, our men were

involved in atrocities too. Those bells were used to make the

attack against our troops (Brooke 1997: A6).

Genealogy of Fantasy

For whom the bells toll is a question that has been answered by

John Donne, Hemingway, and others. It is a question Kidlat Tahimik

revived in 1975-77 when he was composing Mababangong Bangungot (my

literal translation is Fragrant Asphyxiations). The background is

significant. It was the period of the Marcos dictatorship

characterized by the wanton violation of human rights and the

plunder of the economy by foreign corporations aided by comprador

oligarchs and semi feudal landlords. It was a regime of violence

sanctioned by the U.S. government which subsidized Marcos and his

Pentagon-advised generals with an average of $100 million foreign aid

from 1972 to 1986. The assassination of Benigno Aquino, and the

return of the old ruling elite has reinforced the neo-colonial

stranglehold of the United States, making The Perfumed Nightmare

less a retro, nostalgic film than a reminder of what has been

missed or forgotten.

At the center of the film is the image of the bridge passageway of

animals, people, and machines connecting past and future, reality

and dream, countryside and city, tradition and modernity. It also

symbolizes for Kidlat, the narrator-protagonist, the ever-present

possibility of self-fulfilment: I chose my vehicle and I can

cross all bridges. Werner von Braun and space travel (from the

Philippines to France and Germany) form part of the cluster of

themes expressing the drive to modernity, or in general the

impulse to transcendence. Space-time compression, the assertion of the

national right to self-determination, and the affirmation of

community intersect in Kidlat's dream of journeying to the United

States, the site of Cape Canaveral and the Statue of Liberty.

The dream of space travel aborts into an escapade in Europe as

petty bourgeois middleman. Kidlat becomes a willing captive of the

American businessman whose chewing-gum machines evoke the myth of

entrepreneurial individualism associated with the figure of Werner von

Braun. But soon the bridge metamorphoses into enclosed spaces of

escalators, fortress interiors, and narrow urban streets,

impelling Kidlat to fantasize: his jeepney becomes a winged horse

traversing boundaries and flying above the ruins of modernized

Europe.

The trope of the bridge easily links the local and the global,

individual and society. It is a marker of continuity amidst

change. Associated with it are the image and voice of Kidlat's father,

veteran of the revolution against Spanish colonial tyranny, whose

absence marks the substitution of authority figures in the film.

Kaya, the hut builder, evokes his independence and creativity. His

father's revelry at managing a horse-drawn vehicle anticipates

Kidlat's gusto as jeepney driver around whom secular and sacred

activities gravitate.

Tragedy evolves into a bizarre metamorphosis of images. After the

father is killed on the San Juan bridge in August, 1898, the

incident which sparked the Filipino-American War, the mother gives to

Kidlat the figure of a wooden horse carved from the butt of his

father's rifle. This symbol of revolt then appears perched on the

front of his jeepney, occupying center-stage at the last sequence

when Kidlat returns to the supermarket after blowing away leaders

of the industrialized West at the farewell party of his American

patron; it appears in the last shot when the mother closes the window

of the nipa hut and foregrounds the wooden horse atop the toy jeepney

Kidlat gave to his sister. His fathers presence, mediated by Kaya

and the mother, signifies the desire for autonomy and freedom, the

weapon of his breath likened to the winds blowing from Amok

mountain, an immanent force of nature.

Tragedy evolves into a bizarre metamorphosis of images. After the

father is killed on the San Juan bridge in August, 1898, the

incident which sparked the Filipino-American War, the mother gives to

Kidlat the figure of a wooden horse carved from the butt of his

father's rifle. This symbol of revolt then appears perched on the

front of his jeepney, occupying center-stage at the last sequence

when Kidlat returns to the supermarket after blowing away leaders

of the industrialized West at the farewell party of his American

patron; it appears in the last shot when the mother closes the window

of the nipa hut and foregrounds the wooden horse atop the toy jeepney

Kidlat gave to his sister. His fathers presence, mediated by Kaya

and the mother, signifies the desire for autonomy and freedom, the

weapon of his breath likened to the winds blowing from Amok

mountain, an immanent force of nature.

The film-maker intervenes. We hear the refrain: When the typhoon

blows off its cocoon, the butterfly embraces the sun. Messenger

from the domain of the rural third world, Kidlat blows through the

chimney of the supermarket, transforming the fragment into a rocket like

apparatus that dismantles the alienating technology of the modern world

and guarantees the superiority of human will-power against

machinery and business. After this, he declares his independence

and resigns from the Werner von Braun Club which he originally

founded. The credits at the end register the impact of Western

technology around the world in the postcards celebrating Werner von

Braun and space exploration. Has Kidlat really escaped the seduction of

Western technical mobility and differentiation?

Analogues of Uneven Development

Can we hazard formulating a thesis for the film? The Perfumed

Nightmare is, in historical context, an allegory of the Filipino

artist's quest for self-determination and claim to recognition. It

tries to recuperate the suppressed energies of the revolutionary

tradition through parody and ad hoc quotations: for example,

witness the boy scout jamboree where the American delegate was

rebuffed. But this collective project is sublimated in various

ways: in folk religion, in the image of Kaya and the hut builders,

in the circumcision and flagellation rituals, and most memorably in

the long sequence on the Sarao jeepney factory.

In the most famous commentary on this film, the leading American

Marxist critic Fredric Jameson focuses on the quality of Kidlat's

cinematic technique the use of 8mm color movie camera, nonsynchronized

sound, characters from real life, etc.---and the postmodernist bricolage

that evokes the wonderment of sheer reproduction and recognition.

This follows clues suggested by the German philosopher Friedrich

Schiller who once distinguished between poets who create

instinctually and depict reality as is, and sentimental poets who

try to embody an idealized nature in form.

Neither naive nor sentimental, or both at once, Kidlat Tahimik

typifies the artist from an unevenly developed, neocolonized

formation where capital operates in a way different from that in

the metropolitan societies. For example, the demise of handicraft

exemplified by the Zwiebelturm in Germany, or the phasing out of

street vendors in Paris, is vestigial compared to the destruction

of homes and whole forests to make room for a highway in Balian,

Laguna. Tahimik's art registers the symptoms of a cultural

production over determined by capitalist private property (the ice

factory), communal modes of work ( hut building, bayanihan), archaic ideology (flagellation,

patriarchal standard of manhood), petty commodity business (jeepney

transport), and feudal-bureaucratic arrangements (police, martial

law). The film bears in its montage, cuts, shots, lighting, and other

stylistic devices the signs of all these combined modes of production

and reproduction.

Interrogating Orthodoxies

We need to go beyond the formulae of rhetorical analysis and

deconstruction of tropes. Instead of engaging in the customary

hermeneutic gloss on the film (which simply replicates New

Critical formalism in this area), I would like to comment on why the

film text lends itself to a wide variety of interpretations. Can

this film be considered a specimen of third world postmodernism?

What kind of audience-position does it offer and what kind of

reception does it enable? Can we make use of this film as a

pedagogical agency for social enlightenment and transformation?

In short, can Kidlat Tahimik be simply judged on the basis of his

class affiliation, or can his films be deployed for emancipatory

purposes? What follows is a preliminary review of possible

answers.

It seems that what has provoked the animus of Filipino

intellectuals is the kind of colonizing patronage instanced by

Jameson's treatment of The Perfumed Nightmare.

Obviously, Jameson is searching for art-forms and cultural

practices that resist late-capitalist commodification and reification,

hence his theoretical constructs of national allegory, naif,

Soviet sci-fi films, and American conspiracy film genre. His

framework is the totalizing (but not absolutizing) mode of

cognitive, geopolitical mapping by means of which he and other

citizens in the West can find a position to understand the global

relations of forces and grasp possibilities of social transformation in

a time when all spaces (nature, the unconscious, and even the

third world seem to have been pre-empted by the enemy.

Roland Tolentino has competently surveyed the objections to

Jameson's approach and also expressed reservations about certain

of Jameson's observations, for example, the conversion of the jeepney

from parody to pastiche, Kidlat as clown, the utilization of body

imagery, and so on. Tolentino is correct in taking Jameson to task

for a literalist instead of the properly historicizing view:

When Jameson mentions that Perfumed Nightmare is not a direct

intervention to Marcos dictatorial regime because of its lack of

connecting images to the regime, he is limited by his lack of a

native informant position. In the film, the town's patron saint is

St. Mark, known locally as San Marcos. The cultural regime

of rituals can therefore be paralleled to the

political culture of the Marcos dictatorship (1996: 123). In

addition, the American boy scout who rides Kidlat's jeepney

(eventually pushed out to the carabao sled at the back), the

figure of the policeman, the reference to discipline and uniformity

echoing a well-known slogan of the martial law regime, the

Marlboro Country billboard in the barren landscape, and others,

all index the atmosphere of regulation under the U.S.-Marcos

dictatorship.

Such traces or indicators escape the understanding of the

hegemonic intellectual unfamiliar with the historical specificity

of the only U.S. colony in Asia. The obsession with a totally

administered and commodified society has obsessed Jameson and Frankfurt

Critical theory to the degree that only a negative dialectics (Adorno)

or a messianic utopian break (Benjamin) can remedy this fatality.

Despite his stress on utopian space, Jameson shares this flaw with

the platitudes of Western Marxism. This time, instead of Kidlat

Tahimik's film being read as a national allegory where the private

dilemma resonates with public meaning, it is selectively construed to

reinforce a first world/third world binary, as already noted by

the aforementioned critics. I am surprised that nothing much is

made of the white carabao (beautiful outside but ugly inside), the

speaking role of the Virgin Mary, and above all the wooden

Pegasus-like horse that becomes an icon at the prow of the jeepney.

The motif of resistance against U.S. imperial domination and liberal

market ideology becomes secondary or completely obscured when the focus

on bodies and Foucauldian genealogy of exoticized details

(circumcision) preoccupy the critic.

Limits of Postmodernist Absolutism

We can adduce here the usual arguments against postality theories

(Ebert 1996). Postmodernism focuses on pastiche and bricolage over

against Bakhtinian multiaccentuality or Brechtian distanciation.

For his part, Jameson enthusiastically celebrates the novelty of a

refunctioned handicraft mode of work inscribed within an

industrialized system of production which distinguishes uneven

development. The film sequence detailing the Sarao factory workers

performing their specific functions and roles in the assembly line

stands out for Jameson as exemplary:

Unlike the natural or mythic appearances of traditional

agricultural society, but equally unlike the disembodied machinic

forces of late capitalist high technology which seem equally

innocent of any human agency or individual or collective praxis, the

jeepney factory is a space of human labor which does not know the

structural oppression of the assembly line or of Taylorization,

which is permanently provisional, thereby liberating its subjects

from the tyrannies of form and of the pre-programmed. In it

aesthetics and production are again at one, and painting the

product is an integral part of its manufacture. Nor finally

is this space in any bourgeois sense humanist or a golden mean, since

spiritual or material proprietorship is excluded, and

inventiveness has taken the place of genius, collective

cooperation the place of managerial or demiurgic dictatorship

(1992: 210).

Jameson's observations are suggestive though somewhat tangential.

As the Filipina critic Felidad C. Lim (1995) has pointed out, this

is not only false to the empirical situation but also a distorted

and misleading interpretation. There is a grain of validity

in her objection. Instead of being cooperative and

pleasure-filled, the Sarao factory is perhaps more alienating and

dehumanized than firms in the notorious free-trade zones since

here semi feudal patronage conceals exploitation, the violation of

minimum-wage labor laws, sexism, and other excesses. What looks

like bricolage is really systematic cannibalizing of dead labor in

the interest of profit. On the surface, this refunctioning of

waste materials can serve to emblematize Kidlat's theme of

converting vehicles of war into vehicles of life. But a long time had

already elapsed since World War II when U.S. army jeeps were first

refunctioned as civilian passenger transport; such jeepneys are

now produced from other sources.

Aside from the ironical innuendo on the duplicity of Sarao, the

film's jump-cut to the toy gift that Kidlat paints for his sister

performs a shift in discursive register. It elides the process in

which the machine changes from a utilitarian or commercial means to a

symbolic one when it travels to Paris and Germany: its last

notable service was to ferry his pregnant wife to the hospital.

The jeep thus indeed becomes a vehicle of life, enabling him to

finally break off from the mystique of Werner von Braun as he

leaves Germany.

Another point may be stressed here. When Kidlat in Paris declares

his independence from America and the West--he resigns from the

von Braun Club--the site where he "blows" away the Western leaders

gazing down on him resembles the old hoary ramparts of San Juan

bridge where his father confronts the U.S. aggressors and meets his

death. What needs underscoring is the running commentary that his

father and millions of Filipinos refused to be bought for $12

million dollars--the price the U.S. paid to Spain for ceding the

Philippines at the Treaty of Paris. An alternative history is thus

proposed.

Something More Beyond Sight

We have already noted earlier the bricolage nature of Kidlat's

cinematic technique. Realist classical cinema flagellants with

bleeding flesh, the block of ice sliding out of the jeep, the

circumcision process, and so on, may be found aplenty here. But the

whole construction of The Perfumed Nightmare may

be described as modernist and avant-garde. It follows Brecht's rule

of interrogating the reason of the status quo by

interrupting narrative, underlining contradictions within an

emerging unity by distanciation and displacement--the

defamiliarization or estrangement of what is accepted as normal,

natural, routine.

This is where Kidlat's films differ from conventional or

commercial productions. The principle of montage and strategic

cuts in the two films serves to question the illusionistic or auratic

power of representation found in classic realist cinema which

interpellates individuals into bourgeois subjects. According to

Stephen Heath, montage aims to overcome mimesis, introspective

psychology, the hero as unified consciousness, and the need for

identification. What critical cinema of this kind seeks is the

ushering of subjects into permanent crisis so that reality can be

questioned and transformed. Aside from montage, the production of

a third meaning through the friction between image and diegesis

(following Barthes' semiotic analysis [1977] ) can be explored.

Kidlat Tahimik follows modernist and avant-garde methods not by

choice but more by necessity. In one interview, he describes his

method of composition:

"The way I make my films is like collecting images; it's like

making a stained glass window. You collect colored pieces of glass

over the years. Today I may find a broken beer bottle, tomorrow I may

find a 7-UP bottle. I'll have all these in a box and maybe two

years later, I start sorting them out and I may find a pattern: if

I like a landscape or profile, I pursue that and I finish the film

by shooting any holes that are still missing in that stained glass

mosaic. Maybe I'm just an accumulator of images and sounds and

then I make tagpi-tagpi [patching up] and sew them together. I just work

with images and I put my sounds on and then I put a flow of thoughts and

start juggling the sequences back and forth. I don't try to

find surrealist images even in the way it happened in Perfumed

Nightmare.

I was a madman when I was making that film and I still am. I

sometimes wonder how certain elements enter the film" (Ladrido

1988: 38).

This craft of allowing found materials may be naive at

first glance, but the spontaneous gathering and invention of

images gives way to the next stage of conscious organizing and

synthesizing. Kidlat Tahimik exploits the objective richness of

his materials, but this does not mean allowing the unconscious or

automatic instinct to take over. In fact, the opposite is the

case: the conscious investigation of experience forces attention

to the modalities of representation. This becomes patent in the

scenes depicting the meeting of the von Braun Club, the passport

picture-taking scene, the ceremony of Kidlat's leave-taking, and so

on.

Stylization and self-referential techniques predominate. Thus

instead of sustained dramatic sequence the longest ones are the

flagellation and circumcision scenes -- we get individual and short

shots combined in an extended temporal structure. This structure

also prevents the formation of aesthetic aura by risk-taking cuts,

as in the shift from wide shots of rice field to Kidlat's sleeping

face, from shots of carabaos in mudpools to the Virgin Mary in

procession, even while continuity is provided by radio

transmission of rocketship launchings, rock music, and the Igorot chant

that sutures disparate scenes together. One result of this

seemingly random splicing is the prevention of boredom or ennui.

The montage seems jerky at times, especially in the sequence of

urban traffic, where repetition of motifs is absent. But the

overall impression is not the polyphony of decontextualized voices

characteristic of post-modern films like Blue Velvet which seek to

recreate the cultural experience of past eras.

Pastiche may perhaps describe the sequence happening in Paris and

Germany where Kidlat ceases to have control over his vehicle (that

is, his life) since its direction is determined by the American

entrepreneur who dangles before the von Braun admirer the bait of a

visit to America, the land of von Braun and rocket ships. But

pastiche is foiled with the counterpoint of an underlying

historicity that is interrupted: the death of Kidlat's

revolutionary father, the loss of control of the vehicle of

independence by Filipinos. This is the unifying theme that

undercuts the temporal discontinuity and generic heterogeneity of

the whole: the potential of decolonization, the possibility of

socialist revolution.

Toward a Tentative Reckoning

It may be instructive to compare The Perfumed Nightmare with Kidlat Tahimik's later film,

Turumba. Mike Feria considers this

latter film technically the best mainly because of a clear

narrative line punctuated with disquieting humor (1988: 36). The

theme of Turumba, as I noted earlier, is the destructive and

unstoppable power of modernization. It unfolds in the change of

the traditional way of life of a family in Pakil, Laguna, who

makes papier-mâché dolls for a living; the family's dream of wealth is

nearly fulfilled at the cost of disrupting their organic solidarity: the

father becomes bureaucratic manager who abandons his role in the

annual turumba festival, the grandmother becomes a quality control

officer.

In hindsight, Kidlat Tahimik believes that it is my smoothest film

to date, more like canvas instead of collage, with color elements

and the sound and everything blending. He also testifies that except

for his nephew Kadu, all the characters are real people who played

themselves in their actual work as blacksmith, cantore, Aling

Bernarda who fixed the clothes of the Virgin, and so on. Kidlat

confessed that he was always fascinated with the blacksmith

because of the way he made Mercedes-Benz shock absorbers into real

beautiful bolos (Ladrido 1988: 42).

In this film Mang Pati, the blacksmith, functions as the

bricoleur , the free spirit, who converts the scrap iron of

rusting Japanese war vehicles left in the jungle into useful

tools. He stands for the independent artisan resisting the

encroachment of the baneful capitalist division of labor that seizes

hold of one family and destroys the enchantment of life centered

on religious ritual and intimacy with nature's rhythms.

A third meaning often insinuates itself when various forms of

signs and sounds the family playing together, the father

conducting the band, the cable transmitting radio and TV signals, the

sounds of nature and traffic intrudes into the unfolding of the

business routine and demystifies its rationality. We are then led

to reflect on the mode of representation as images. characters,

and actions are distanced and displaced from their natural

environment. We begin to discriminate between what is made up and

what pretends to be natural or inevitable.

One more point needs to be emphasized. Despite the ingenious and

witty cuts, the film follows a logic of causality based on the

presence of the market and media of communication (radio, TV,

highway traffic, exchange of goods). The narrative intelligence centered

on the curious and dutiful son of the cantore provides the

unifying consciousness that allows a degree of identification; in

the midst of the accelerated pace of the assembly line production,

the shots are dragged on to suggest psychological introspection. A

voyeuristic element insinuates itself in certain scenes when suspense

develops will the family meet the production deadline? What will happen

to the turumba festival in the absence of the father?

But despite this tendency to classic expressive-realist cinema,

the invocation of a disruptive nature the typhoon winds distracts

us from the failure of the film to present the unrepresentable,

the Munich Olympic festival, scene of international carnage. We are

brought back to the immemorial present: the festival procession of

the Virgin Mary winding back into the cavernous womb of the

church, surrounded by the chanting and singing of the people, the

undying matrix (in Bakhtin's dialogic thought) of vitality,

resourcefulness, creativity. It is not far-fetched to say that

Kidlat Tahimik overcomes the seduction of technology and speed by

a suggestion that what is complete is really uncomplete and

unfinished. In this, Turumba rejoins the pioneering first work in

asserting the auteur's control and shaper of a critical dialectic

based on the transforming movement between production and

representation, the disclosure of social relations as historical

and changeable.

Reverberations from Quiet Lightning

Ultimately, despite his deceptively elitist or naif pose, Kidlat

Tahimik should be judged as an adequate or deficient makeshift

artist mediating between the containment strategy of a nativist

romanticism proud of one's ethnic heritage and a radical critique

of colonial mentalities and neocolonized sensibilities that block

change and liberation of individual potential. To be sure, this

judgment is very hypothetical; Kidlat's career is not yet over, so

the verdict may not be forthcoming for some time yet.

Lacking a full assessment of Kidlat Tahimik's other works and

those in progress, I can only provisionally conclude here by

speculating on what audience position and effects the films may have. So

far the consensus is that Kidlat's films are primarily addressed

to a Western metropolitan audience and critical consciousness.

They have never been commercially shown in the Philippines; only

the government's Cultural Center of the Philippines has

exhibited them at certain times. Our interest approximates the reasons

why, for example, Teshome Gabriel (1994) once speculated on

the possibility of a distinctive third world cinema

patterned after the three stages of the national-liberation

struggle theorized by Frantz Fanon.

However, despite some analogies, I do not think Kidlat Tahimik is

concerned with indigenization, combatting the world cinematic

language of Godard and Coppola (Copolla is his North American

distributor), or vindicating the folk/oral art of the Igorots and other

ethnic groups in which spirit and magic predominate. There is

indeed spatial concentration in both films demonstrated in wide

and panning shots, long takes, graphic repetition of images, with

few intercutting between simultaneous actions, rare close-ups

except for comic touches, with lots of witty juxtapositions and

humorous parodies.

Kidlat's filmic practice, however, cannot be categorized as

'third world' throughout; it is a mixed and unevenly developed

practice which, for the most part, stimulates critical reflection by

techniques of displacement and distanciation. Only rarely does it

summon hypnotic identification with heroic protagonists because

the illusionistic power is always undercut or decentered by the

devices we have noted. Its realism is intermittent, adhoc, conjugated

with stylized self-reflexive gestures and idioms. The

audience-position it allows, I think, will chiefly be sceptical,

inquisitive, and partisan even wrong headedly utopian as Jameson;

it can at best contribute to catalyzing an agency that can raise

consciousness and maybe mobilize a critical mass for the collective task

of radical social transformation. In any case, any thorough evaluation

of Kidlat's cinematic artistry will have to defer to the critical

sensibility of Filipinos who are involved in the process of the

popular struggle for national liberation and democracy--the masses

of workers, women, peasants, intelligentsia, and

professionals--without which art such as Kidlat's films cannot be

properly appraised and fully appreciated.

REFERENCES

Brooke, James. 1997. U.S.-Philippines history Entwined in

War Booty. New York Times (December 1): A6.

Connor, Steven. 1989. Postmodernist Culture. New

York: Basil Blackwell.

Ebert, Teresa. 1996. Ludic Feminism and After. Ann

Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Ellis, John. 1981. Notes on the Obvious. In Literary Theory

Today.

Eds. M.A. Abbas and Tak-kai Wong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong

University Press.

Feria, Mike. 1988. A Kidlat Tahimik Retrospective. Kultura

1.1: 33-36.

Gabriel, Teshome. 1994. Towards a Critical Theory of Third

World Films. In Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory

Eds. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman. New

York: Columbia University Press.

Heath, Stephen. 1992. Lessons from Brecht. In Contemporary

Marxist Literary Criticism. London and New York:

Longman.

Jameson, Fredric. 1992. The Geopolitical Aesthetic:

Cinema and Space in the World System. Bloomington: Indiana University

Press.

Ladrido, R.C. 1988. On Being Kidlat Tahimik. Kultura 1.1:

37-42.

Lim, Felicidad. 1995. Perfumed Nightmare and the Perils of

Jameson New Political Culture. Philippine Critical Forum 1.1:

24-37.

Nichols, Bill. 1981. Ideology and the Image.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Tolentino, Roland. 1996. Jameson and Kidlat Tahimik.

Philippine Studies 44 (First Quarter): 113-125.

Vizmanos, Danilo. 1989. The Balangiga Incident.

Midweek (September 27): 11-14.

E. SAN JUAN, Jr. was recently

visiting professor of literature and cultural studies at National Tsing

Hua University in Taiwan and lecturer in seven universities in the

Republic of China. He was previously Fulbright professor of American

Studies at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium, fellow of the

Center for the Humanities at Wesleyan University, and chair of the

Department of Comparative American Cultures, Washington State

University.. Among his recent books are BEYOND POSTCOLONIAL THEORY

(Palgrave), RACISM AND CULTURAL STUDIES (Duke University Press), and

WORKING THROUGH THE CONTRADICTIONS (Bucknell University Press). Two

books in Filipino were launched in 2004: HIMAGSIK (De La Salle

University Press) and TINIK SA KALULUWA (Anvil); his new collection of

poems in Filipino, SAPAGKAT INIIBIG KITA AT MGA BAGONG TULA, will be

released by the University of the Philippines Press in 2005. A shorter

version of this article may be found in my book AFTER POSTCOLONIALISM

(Rowman and Littlefield, 2000).

E-Mail address of the author:

http://[email protected]

It can be said that Kidlat's films all deal with memories of

creation and destruction. They embody historical recollections of

the national past accompanied by a critical inventory of what is

important and meaningful to be saved for the future. This essay

intends to explore the method in which the colonial past of

Filipino society, its current crisis, and problematic future has

been translated into visual tropes and symbolic figures in

Kidlat's two films, Mababangong Bangungot (Perfumed Nightmare, 1977, 91

minutes, winner of the International Critics Award at the Berlin Film

Festival Award), and Turumba (1981-83, 94 minutes,

winner of the Top Cash Award, Mannheim Film Festival). My comments are

meant to provoke questions and arouse interest in the topic of what

constitutes a properly Filipino cinema.

It can be said that Kidlat's films all deal with memories of

creation and destruction. They embody historical recollections of

the national past accompanied by a critical inventory of what is

important and meaningful to be saved for the future. This essay

intends to explore the method in which the colonial past of

Filipino society, its current crisis, and problematic future has

been translated into visual tropes and symbolic figures in

Kidlat's two films, Mababangong Bangungot (Perfumed Nightmare, 1977, 91

minutes, winner of the International Critics Award at the Berlin Film

Festival Award), and Turumba (1981-83, 94 minutes,

winner of the Top Cash Award, Mannheim Film Festival). My comments are

meant to provoke questions and arouse interest in the topic of what

constitutes a properly Filipino cinema.